The Left is Insane and The Right is Retarded

Modern politics is less a contest of ideas than a collision of instincts — the impulse to change and the need for order, each vital to civilization, yet fatal in excess.

ARipstra (WMF), CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

I once read somewhere a quip saying that “The Left is Insane and The Right is Retarded.” And I have loved this quote ever since. I must admit that I have many times encountered situations in which this seemed a very fitting way of perceiving the dispositions of the two main sides of the current political conflict. But is it actually true? Of course, this particular bonmot is completely hyperbolic, but is there, as with many hyperbolic stereotypes, some actual substance behind it? Are liberals more intelligent than conservatives, and are conservatives more mentally stable than liberals? And if so, what does that imply for our current historical era?

To start off, the available data imply that yes, there is some substance behind these claims. There is an abundance of data (I won’t link all the studies here, but it is really simple to find a number of them within a couple of minutes) from several Western countries showing that intelligence is positively correlated with social liberalism and negatively correlated with social conservatism and authoritarianism. On the economic front, the findings are much less robust and clear-cut, yet there still seems to be some positive correlation between economic liberalism/social conservatism and intelligence.

Most detailed data come from the United States, where among non-Hispanic whites, people self-identifying as extremely liberal scored 8.5 IQ points higher than people self-identifying as extremely conservative — that is a big gap indeed, similar, for example, to the gap between a Western European country and a country in Southeast Asia. These “extreme” groups are relatively small parts of the overall population of the country, so if we simplify it to liberals and conservatives among non-Hispanic whites, the IQ gap would be about 4 IQ points in favor of the liberals — not huge, but relevant. (Once again, this is only among the non-Hispanic white population; non-whites are pulling the overall Democratic/liberal average down.)

I do not have any new revealing data to present, but purely from the point of view of my lived experience in the Czech Republic — a country whose political spectrum is slowly but surely becoming westernized in many aspects — I can confirm that people I personally know who incline toward the progressive left tend to be intelligent. I know many of them personally, and although I usually wildly disagree with their political opinions on almost everything, I must also objectively admit that they are never stupid people — usually college-educated professionals such as IT workers, architects, or people of that sort. (This will surely be skewed by the general composition of my social network, which is heavily tilted toward young, urban, college-educated people.)

In the Czech parliamentary elections that just took place two weeks ago, the two parties that are the most socially liberal (the Pirate Party and STAN) got 20% of the vote. In “trial” elections held only among college students a couple of weeks before the real elections, these two parties got over 50% of the vote.It is an established fact that intelligence and the level of attained education correlate very strongly, which means that among the most intelligent strata of Czech youth, socially liberal parties clearly dominate disproportionately. Available data show that even students majoring in what are often perceived as “useless leftist” subjects, such as sociology or fine arts, have comfortably above-average IQ. There is a study from Germany researching the association between intelligence, party identification, and political orientations — the parties with the highest-IQ voters were the Pirate Party, the Greens, and the Free Democrats, all socially liberal parties.

These findings lead some, for example Dr. Nathan Cofnas (in the U.S. context), to conclude that the reason for the crushing preeminence of liberal/progressive/woke ideas in the “opinion-making institutions” is, first and foremost, the simple fact that the people who are really ideologically committed (the extreme liberals) are on average just more intelligent than the people who are really ideologically committed to conservatism. And yes, I think there certainly is a substantial degree of truth in that claim.

Now this is obviously not an easy truth-pill to swallow as a, broadly speaking, right-wing person. What does this say about our side of the socio-political/value conflict in the West? The most obvious way in which many right-wingers might try to debunk this view of progressive dominance within Western ruling institutions is by saying that it is not caused by meritocracy promoting the most intelligent or capable person, but by systematic ideological nepotism.

Now, first of all, it is amusing that when, for example, a black person in America suggests that their disadvantaged position in society is not caused by possible IQ differences but by systematic racism, right-wingers laugh at this as a massive cope. Yet when there is a suggestion that their own disadvantage in an ideological struggle might also be caused by intelligence difference between the two sides of the conflict, suddenly theories of “systematic” disadvantage within the system do not sound so bad. IQ realism cuts both ways.

But jokes aside, there surely is some degree of truth in this claim. Once some form of dominance in institutions is established, it becomes relatively easy to enforce ideological dominance that is definitely not based on meritocracy -Noah Carl calculated that if sociology professors in U.S. faculties were selected purely on the grounds of verbal IQ, there would be a non-negligible yet relatively modest liberal advantage instead of the complete dominance that exists today. More subtle explanations suggest that more intelligent people are better able to discern the power dynamics and prevailing ideological atmosphere within the institutions they enter, and are therefore more likely to conform to the dominant — progressive — ideology. However, it is also important to admit that in order to be effectively nepotistic, you need to be capable and intelligent in the first place.

People on the right often talk about the success of Jews or possibly Indians in various fields being caused primarily by their nepotism instead of high capabilities resulting from very high average IQ among Ashkenazi Jews or among the highly selective upper-class Indian immigrants. (To be fair, I never really researched this particular topic of nepotism deeply, so who knows — I do not have a strong opinion.) But once again, you can’t really “nepotism” your way up without being highly capable in the first place. The initial high level of presence within the upper echelons of relevant institutions must first be established, and competing ideological forces — which are also undoubtedly trying to expand their influence within these institutions — must be suppressed. To achieve this, alongside nepotism, there must also be intelligence and competence.

To provide an example, if the Gypsies in Central and Southeastern Europe decided they would use strict ethnic nepotism to slowly dominate the respective state institutions responsible for the redistribution of welfare in order to improve their economic position, would they succeed? Would they be able to establish themselves as the leaders of relevant departments within ministries and within the political parties on the left, where they would get elected to political functions from which they could somehow influence the levers of power and the flow of finances? Well, of course not, since there simply aren’t nearly enough Romani people with sufficient education to penetrate such institutions and effectively alter their functioning. Even though in some countries, such as Slovakia, Gypsies likely constitute over 10% of the population — a similar percentage to that of Black Americans — their political footprint is largely nonexistent. (Whether this inability to produce an educated nomenklatura is due to genetic causes, cultural causes, discrimination, or some combination of these is irrelevant for this argument.)

But another, maybe even more important, question is: why are more intelligent people drawn toward leftist/progressive ideology? Here I have my doubts about the explanation provided by Nathan Cofnas, who says the following:

“To explain the appeal of leftism—which increasingly takes the form of wokism—you have to explain what wokism is. I argue that wokism is simply what follows from taking the equality thesis of race and sex differences seriously, given a background of Christian morality. Both the mainstream left and right believe that innate cognitive ability and temperament are distributed equally among races, and probably the sexes, too. (Mainstream conservatives acknowledge the existence of physical sex differences, but they rarely chalk up disparities in, for example, mathematical achievement to differences in innate ability—at least not publicly.) As I will explain, wokesters correctly follow the equality thesis to its logical conclusion, whereas conservatives fail to recognize the implications of their own beliefs. Smart people are disproportionately attracted to wokism in large part because it offers a more intellectually coherent explanation for the major issue of our time, which is the persistence of racial disparities.”

This implies that the political opinions of people are molded mostly by some kind of rational, logic-based evaluation. I think this is, on the population level, a dubious claim. In his book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, the evolutionary psychologist Jonathan Haidt claims that people’s beliefs are driven primarily by intuition, with reason operating mostly to justify beliefs that are intuitively obvious.

Jonathan Haidt’s concept of the “rationalist delusion” challenges the Enlightenment idea that human beings are primarily rational agents guided by reason. In his metaphor of the elephant and the rider, the elephant represents our intuitive, emotional mind, while the rider symbolizes conscious reasoning. The rider believes he’s in control, but in reality, he mostly just rationalizes the elephant’s movements — constructing post hoc justifications for intuitions that arise automatically. Haidt argues that moral and political beliefs are largely shaped by these deep-seated intuitions, and that reason functions more as a lawyer defending them than as a judge impartially weighing evidence. The “rationalist delusion,” then, is the belief that human reason alone can deliver moral truth or social harmony, when in fact our reasoning is deeply dependent on and limited by our moral intuitions and group loyalties.

In other words, when a person is confronted with some ideological position that does not have an empirically correct asnwer but is dependant upon a value judgement — for example, should abortion be legal — their brain produces an unconscious intuitive response, which they then consciously, using logic and reason, legitimize.

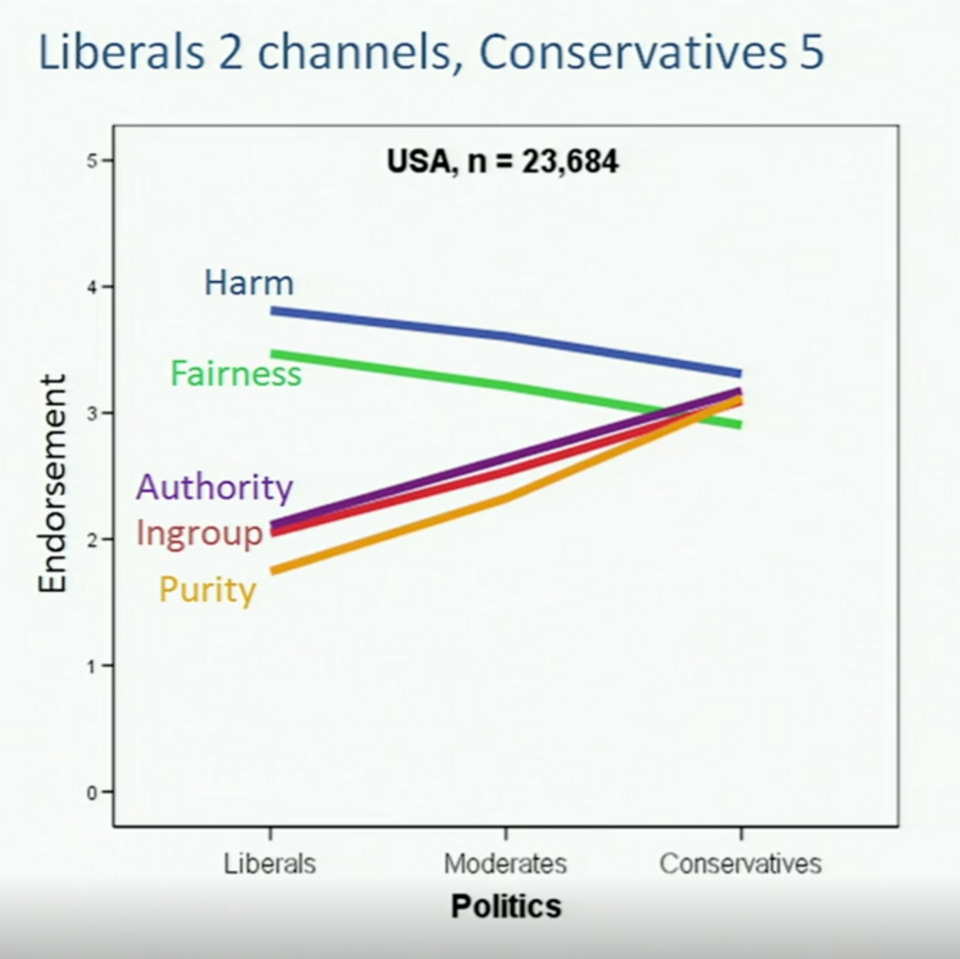

Moreover, Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory proposes that human morality is built on several innate psychological systems — commonly identified as Care/harm, Fairness/cheating, Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, and Purity/degradation (with Liberty/oppression often added later). These moral “taste buds” evolved to help groups cooperate and survive, but individuals and cultures emphasize them differently. In modern politics, liberals tend to prioritize the individualizing foundations of Care and Fairness, focusing on harm reduction, equality, and autonomy, while conservatives draw more evenly on all foundations, especially the binding ones — Loyalty, Authority, and Purity— which stress cohesion, tradition, and moral order. This difference helps explain why liberals view conservatives as insensitive or oppressive, and conservatives view liberals as naïve or morally unanchored: each side is guided by a distinct moral palette rooted in evolved intuitions rather than pure reason.

I would suggests that the stronger attraction of contemporary progressive ideas among intelligent people — a pattern visible throughout history, as various forms of Marxism once drew many of the brightest minds — is best explained by the cross-correlation between intelligence and certain personality traits, most notably Openness to Experience and a general preference for novelty and change. These traits are themselves associated with the moral foundations most closely linked to social liberalism, such as Care and Fairness.

In my view, the liberal tilt of higher-IQ individuals does not arise because intelligence reveals objective political truths, but because intelligence and Openness tend to co-vary. This shared disposition makes liberal moral and aesthetic orientations more psychologically appealing. More intelligent individuals are then simply better equipped to rationalize, articulate, and defend these predispositions in abstract and persuasive terms — which, in turn, makes progressives particularly effective at shaping and maintaining dominance within the “opinion-making institutions” of modern society.

Jonathan Haidt, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

I am by no means the first person to make this connection, but the claims of Jonathan Haidt must inevitably make one think of Vilfredo Pareto’s theory of psychological residues. Pareto, an Italian sociologist and economist publishing a century ago, claims that beneath people’s stated beliefs and ideologies lie stable, instinctive dispositions that shape behavior far more than conscious reasoning. These “residues” are enduring emotional and psychological drives — such as the desire for stability or the attraction to novelty — while the ideological doctrines and rationalizations people construct around them are merely “derivations.” Pareto argued that societies move through recurring cycles as different elite types alternate in power. Periods dominated by “lions”—strong, disciplined elites who rule through authority and tradition—bring order and stability but eventually stagnate due to rigidity. They are then replaced by “foxes,” cunning and adaptable elites who govern through persuasion, finance, and manipulation. Under their rule, society becomes dynamic and prosperous but gradually descends into corruption and moral decay. When the foxes grow too decadent to maintain control, new “lions” arise—often from outside or lower strata—to restore order through force, beginning the cycle anew.

Building on this, the distinction between Pareto’s lions and foxes is not merely about different governing techniques but about contrasting psychological worldviews. Lions embody the moral psychology of order and loyalty — they believe in fixed truths, sacred hierarchies, and the power of duty. Their strength lies in moral clarity and collective discipline, which can hold societies together during times of crisis. They are represented by figures like military rulers, monarchs, or clerical hierarchies — from the Roman legions and medieval knightly orders to the Prussian officer class or twentieth-century nationalist strongmen — who defend stability through obedience and sacrifice. Foxes, by contrast, operate through skepticism and calculation; they distrust absolutes, preferring negotiation, innovation, and the manipulation of symbols to direct force. They appear as court intriguers, financiers, and modern technocratic politicians — from Renaissance diplomats like Machiavelli or Talleyrand, to contemporary media-savvy elites and corporate managers — who rule by persuasion, deal-making, and control of information. Their intelligence is fluid rather than principled, valuing adaptability over constancy. Where lions derive legitimacy from faith and order, foxes maintain control through narrative and illusion — managing perception and manufacturing consent rather than enforcing obedience. Each represents a vital but opposing moral energy within civilization: the lion’s instinct to preserve and the fox’s impulse to transform.

Vilfredo Pareto

Now, first of all, it is clear that Pareto was able to sort of intuitively vibe out something that empirical research done by Haidt has confirmed to be true a century later — that we are mostly driven by intuitive evolutionary impulses dictating our moral preferences, and we then use our intellect, facts, and logic to most effectively rationalize those preferences.

Secondly, the description of the two types of elites — the foxes and the lions — seems to be somewhat applicable to the moral foundations prevailing among current Western liberals and conservatives, especially the lack of the so-called binding values of loyalty, authority, and purity among liberals in contrast with conservatives.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Kaiser Bauch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.